Field workability. It’s difficult to quantify, because whether it’s a good time for field work depends on the work you’re trying to do, your equipment, your soil type, as well as maybe your tolerance for compaction and the other time-sensitive elements of the farm system. But lots of growers using soil health practices describe being able to do the work they needed to in more diverse conditions.

For example, Vance Johnson, a farmer in Wilkin County, MN, described in a recent talk how he was able to finish planting in a light rain in a reduced-till field with lots of residue, while in a conventionally tilled plot he could barely make it to the end of the field to get out, and still had a lot of clean up to do.

Many may recall the difficulties associated with field wet spring and fall field seasons in 2016 or 2019. In Minnesota, precipitation between the 1950s and 2018 has increased by 10-25% across the state, with the most dramatic differences happening in southern Minnesota. Extreme precipitation events of 2 inches or more have also increased in frequency over time. Annual precipitation is expected to continue to increase over time, with the largest seasonal increases likely during fall and spring. With a shortening window of conditions favorable for getting in the field, building soil structure using soil health practices and opting for precision ag equipment may help you get into the field sooner rather than later.

These timely operations can sometimes make a big difference to agronomic outcomes. Corn and soybean yield goes down with delayed planting in the spring. Spraying herbicide in the critical weed control window can also protect yield. Just as importantly, getting field work done when you’re ready can reduce stress and improve quality of life on the farm. If you’re able to follow through on a plan more often, that makes it easier to attend family events, and feel more in control of the farm/life balance.

So how many days do we have? The best source of field workability data is from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. This is based on a county level expert who reports a number of days suitable for field work each week April-November in Minnesota. This shows up right on top of the weekly MN Crop Progress Reports (you can subscribe from the USDA) as a statewide average.

More locally, the staff at the University of Minnesota’s Southwest Research and Outreach Center (SWROC) at Lamberton have been recording field working days daily between April and November since 1974. They also record soil moisture every two weeks. Dr. Bill Lazarus, a UMN Ag Economist, has used that data to build a simple model that predicts field workability based on soil moisture for that location.

You can also calculate field workability using a “50-50” rule , which states that “at water contents around field capacity, traffic on agricultural soil should not exert vertical stresses in excess of 50 kPa at depths >50 cm.” By using soil moisture readings and calculating the vertical stress for a particular implement, you can identify a threshold for days when you should not traffic your field. Using this rule, a study from Katie Black and Samantha Wells found that even relatively light implements, like a high clearance tractor, could only operate for a third of the days in a fall cover crop sowing window (late July - late October) without risk of damage to soils in a very wet fall season.

Table 1. Predicted vertical stress and subsequent trafficable days by interseeding implement at Waseca, MN in 2018 and 2019

|

Implement

|

Mean

ground

pressure

|

Predicted

vertical

stress

|

Trafficable days 2018

|

|

Trafficable days 2019

|

|

|

--------kPa--------

|

Jul.

|

Aug.

|

Sept.

|

Oct.

|

Total

|

Jul.

|

Aug.

|

Sept.

|

Oct.

|

Total

|

|

|

Rowbot

|

337.0

|

162.7

|

13

|

31

|

30

|

29

|

103

|

13

|

31

|

30

|

29

|

103

|

|

|

Avenger

high-clearance

tractor

|

34.5

|

45.9

|

2

|

31

|

0

|

14

|

47

|

0

|

7

|

11

|

13

|

31

|

|

|

M-18 Dromader

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

15

|

22

|

17

|

64

|

6

|

20

|

16

|

18

|

60

|

|

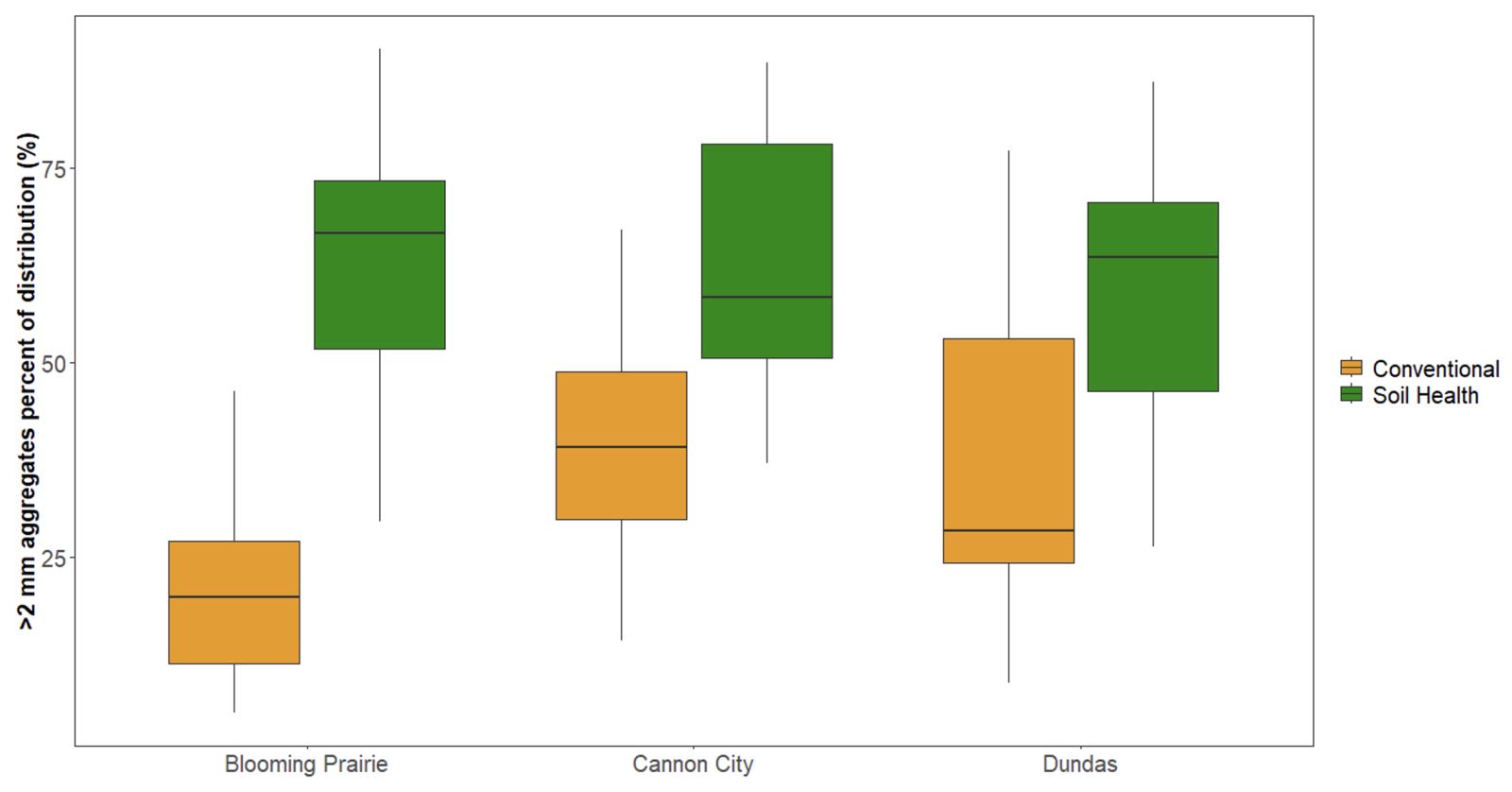

In a recent study in Southern MN, Cates and Tangen explored the root causes of easier field access in a soil health system: was the soil drying out faster, or did it have better structure? How did that structure respond to rain? On the physical side, we found distinct increases in large soil aggregates with reduced tillage. These large aggregates, like larger bricks in a building, carry heavy equipment more easily than smaller soil aggregates. We didn’t see evidence of faster infiltration in reduced tillage systems, or faster drying after a rain. So we have stronger evidence that more field working days might come from better physical structure. Since the soil health systems were rarely drier than the conventional systems, we wouldn’t have calculated any difference in working days using the formulas described above.

Photos: Differences in soil structure were visible on the surface, as the soil health field was covered with residue and appeared crumbly and dark, while the conventionally tilled field was lighter colored and crusted on top.

Figure 1. Over the 2022 and 2023 growing seasons, we found more large soil aggregates in fields using soil health practices (reduced tillage, longer rotations, some cover cropping)

We also surveyed soil health farmers to see whether the anecdotes of getting into the field earlier were part of a widespread phenomenon. Most farmers who identified themselves as “soil health” managers said they got into the field at the same time as conventional neighbors. But they said they got into the field earlier than they had when they had previously farmed conventionally. That mixed signal may be due to poor memory, or unwillingness to speak ill of their neighbors. Many soil health farmers surveyed also indicated that they had increased their quality of life, including 67 percent who had greater optimism for the future and 40 percent who had lower stress after they started using soil health management systems. Farmers shared that they had lower stress, more time with their families, and less financial worry after their transitions to soil health management systems, though these observations weren’t quantified.

These data aren’t conclusive, but they suggest that farmers can get a little more control over when they get field work done when they reduce tillage and build soil structure. Heading into the stressful spring season, we wish everyone a smooth and efficient planting, with rain only the night after the crop is in.

The authors wish to acknowledge the Watershed Innovations (WINS) Grant Program for their generous support.

(Anna Cates is an Extension soil health specialist; Katie Black an Extension educator, climate adaptation & resilience; Bill Lazarus an Extension economist; Amit Pradhananga, Department of Forest Resources Center for Changing Landscapes; and Bailey Tangen, Extension educator, water resources & soil health.)