You can hardly escape talk about water—especially irrigation water—and the drought that has gripped much of the western United States the past few years.

But even in drought conditions there are things growers can do to help their irrigation practices and efficiencies. So says David Tarkalson, research soil scientist/cropping systems agronomist with the USDA’s Northwest Irrigation and Soils Lab based in Kimberly, ID.

Tarkalson, speaking at the University of Idaho Snake River Sugarbeet Conference in mid-December, offered his ideas, based on years of research, at the event.

Tarkalson acknowledged everyone in the room knows their crops need water. He said, “We also know that we have come a long way in terms of technologies and we need to make the best use of the technology we have. And the great thing is lots of research and development went into irrigation, irrigation systems, understanding how to irrigate, understanding how much water plants are using—information they never used to have before. And that information knowledge base is growing and growing. And to be effective economically and environmentally, we need to really take advantage of technology.”

He pointed out another reality that sometimes gets lost in lean years as well as in years of plenty. Referring to the ongoing drought, he said, “This is a continual thing. There are years of drought, there are years of plenty. Last year we had some restrictions, some water shortages. And these things are going to continue.”

In outlining the four areas he planned to cover, Tarkalson said, “We’re really focusing on several different things including the irrigation system itself. How can we make sure that we’re efficient at putting water on and putting it on uniformly? Knowing how much we’re putting on and reducing all the inefficiencies that easily creep into a system? Once we tighten that up and combine that with this interaction with the soil system, understanding our soils, our rooting depth, how much water our soil can hold, how to manage that water in that soil crop system - then we're going to be able to easily dial in our water applications and prevent under application and over application and all the issues associated with that.”

He added, “The nice thing is all this information with today’s technology is available. All the crunching of the numbers, the math and the data management can all be done within existing systems and software that are basically free.”

The four areas Tarkalson focused on were:

1 – Irrigation system

- Water making it uniformly on the field

- Knowing how much water is being applied

- Reducing sources of inefficiency

2 – Soil system

- How much water can the soil hold?

3 – Crop information

- Key dates (emergence, full cover, harvest estimates)

- Effective rooting depth

4 – Technology helps

- Web and apps, soil water measurement equipment

Irrigation System

“So we know that the best equipment will do a poor job with bad management,” he said. He then showed several photos of leaking irrigation pipes, fields where irrigation was not uniform, i.e., dry spots, well irrigated spots, etc. “Do we know what our systems are doing? Do we have issues out there? Do we have leaks?”

He added, “Make sure your nozzles, your pressure regulator systems, the pressure in your system are all maintained and evaluated before you start the season. It's easy to put the wrong nozzles on.”

Tarkalson also touched on pivot end guns. “There’s lots of data showing the end guns are extremely inefficient at applying water. If you want to increase your efficiency without doing much at all, just turn off your end guns. Automatically, your efficiency will go up 10 percent at least.” Tarkalson spoke about nozzle height on pivots, showing a photo of a pivot running in a fairly stiff wind. “These nozzles are set high in the air. You're going to lose a lot of that water. That water actually coming out of the nozzle is not making it into the soil. It's evaporating and blown off, which is extremely inefficient. You can improve this by dropping the nozzles down. But then you have got to make sure that your application rate is matching your infiltration rate. If you don't do that, then you're inefficient.”

If your ground is hilly or has many slopes, Tarkalson said, you might want to consider methods/practices that will help keep water in place until it can soak into the ground. He pointed to a Dammer Diker as one method to help alleviate this problem and allow growers to put more water on compared to watching it run down the rows because the ground can’t absorb the water being applied. Today’s pivots and linear systems “put so much water down so quickly you want to capture that and get it into the soil. That's the key.”

Soil System

Moving on to the soil system, Tarkalson said, “You need to know how much water to put on and when to put it on so that you're not leaching.”

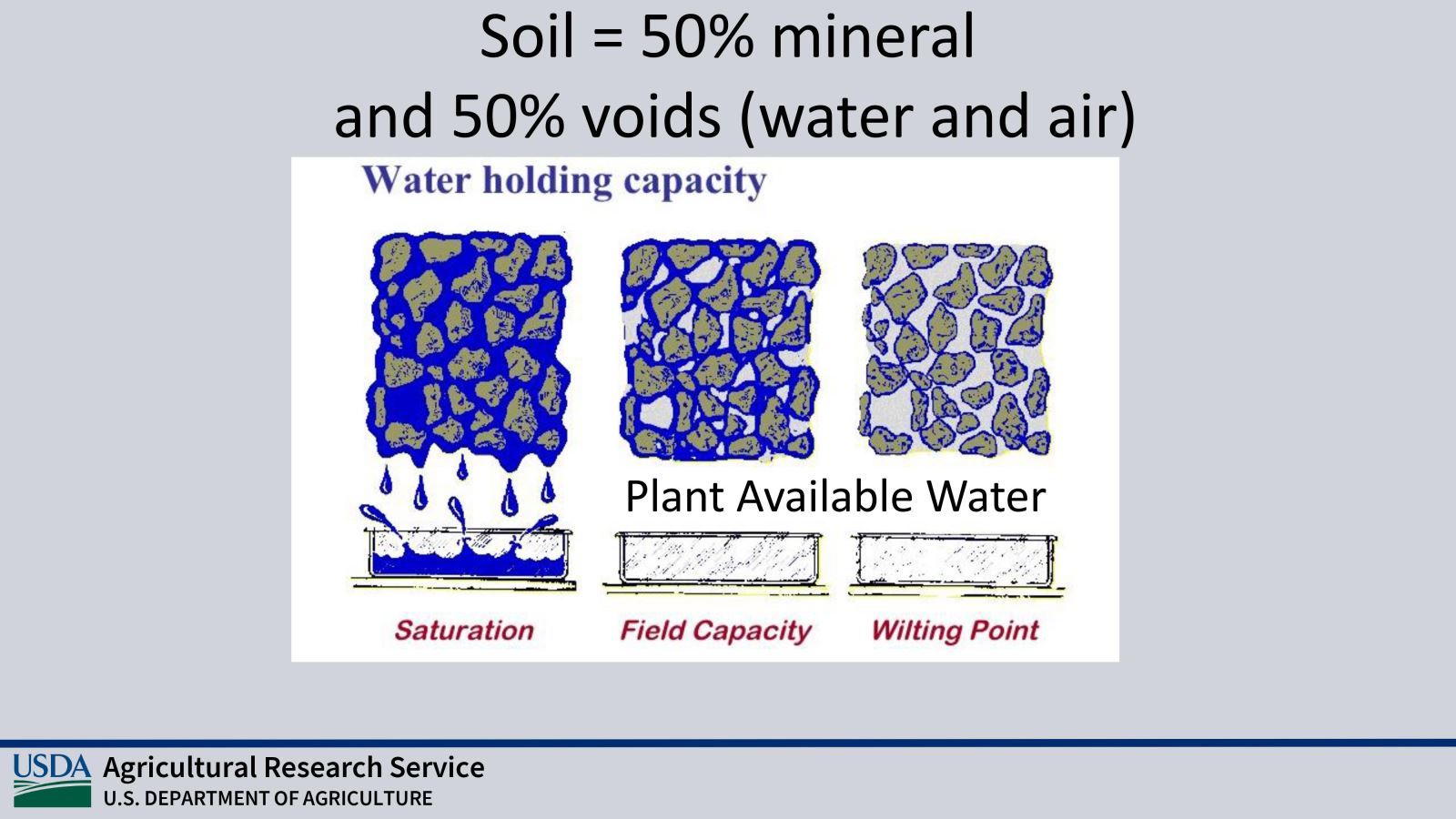

Three parts of the soil water holding capacity he talked about were saturation, field capacity and wilting point. Think of a column of soil, he said. “Fifty percent of that volume is air and 50 percent, on average, is solid material. That’s a porous material. It’s a sponge. When you fill all that up, there’s no water that can fit in there. That’s called saturation. That happens right after an irrigation or heavy rainfall in the top foot of soil.”

He continued, “Now that soil has a charge to it, an electrical charge to it. It’s a net negative charge and water actually has a net positive charge to it. Therefore, it’s trapped in the soil. Some of that water will stay in that soil and won’t be affected by gravity.”

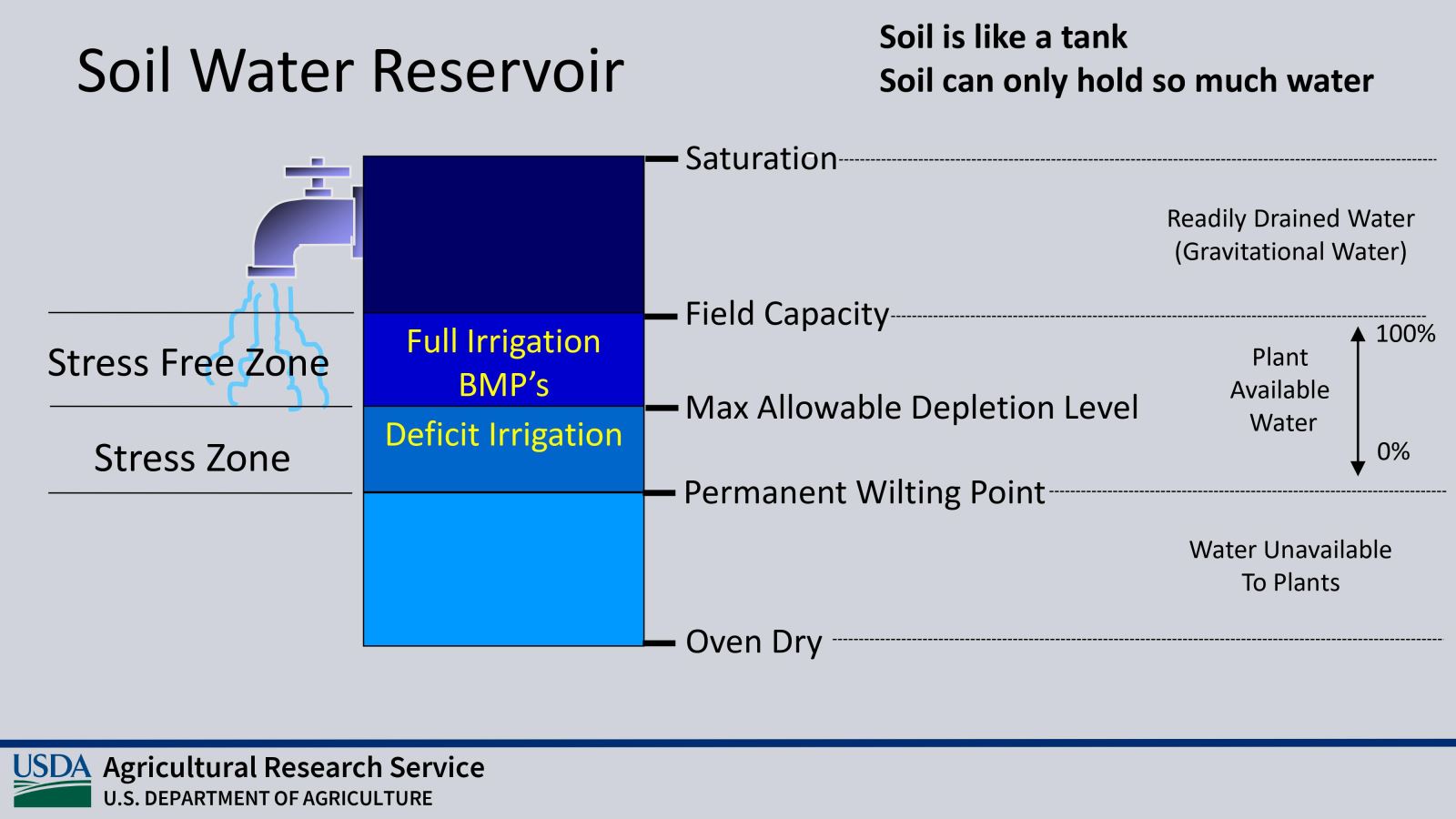

Once you get to that point where that soil is holding as much water as it can, that term is called field capacity. (Figure 1) Water all the way down to a point called permanent wilting point is one extreme that growers need to be aware of. “That's the point where there's still water in the soil, but the plant can no longer effectively retrieve that water and the plant wilts or dies or becomes very low-performing. So a plant can actually extract water from the soil between these two points of soil water content. That's one important thing to remember there.”

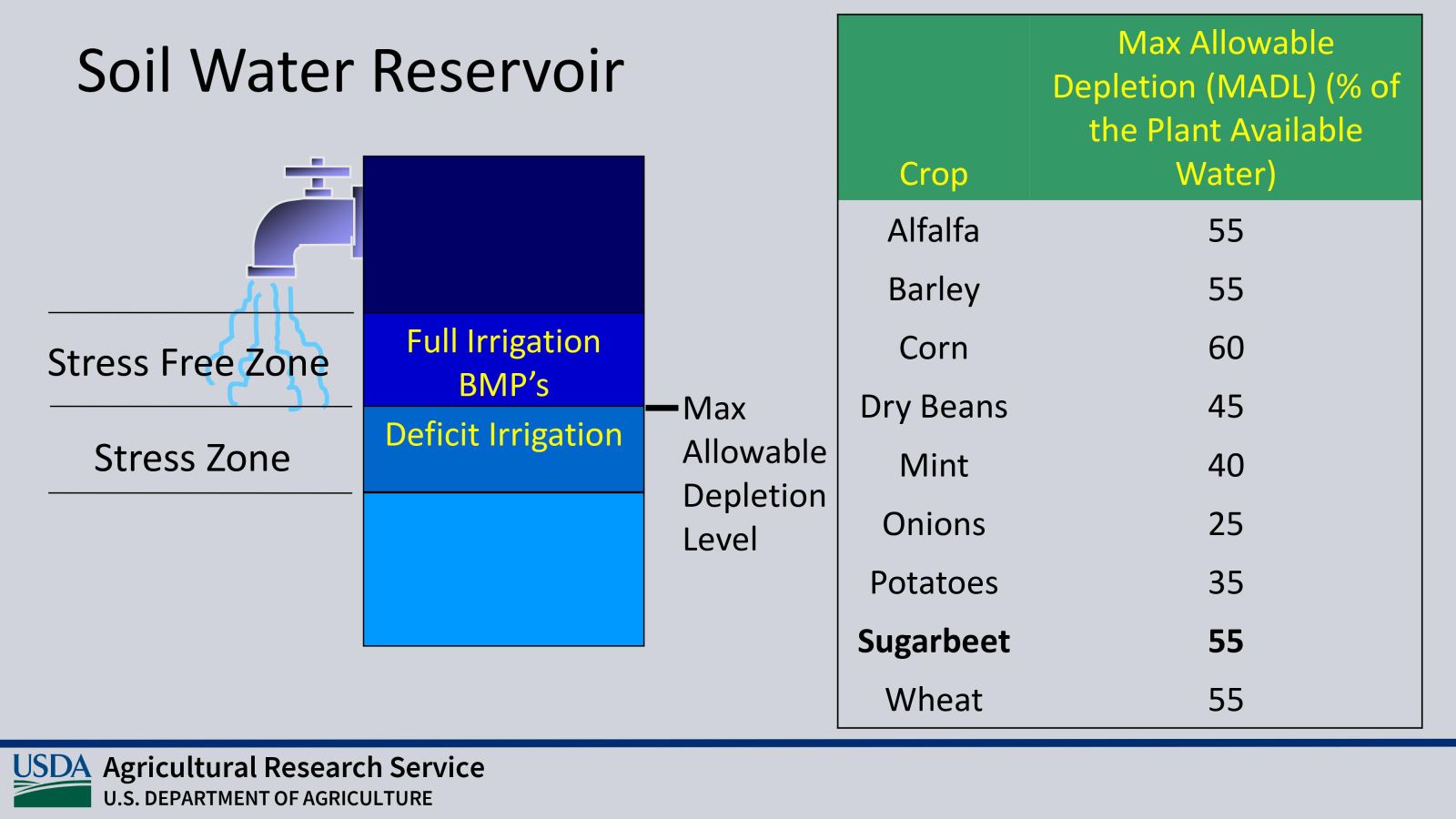

(Figure 2) “Once you get to field capacity down to permanent wilting point, that's what we call plant available water,” he said. “However, to maintain a stress-free environment, you can only use a fraction of that water before the plant goes into stress. And that’s different for different crops.” (Figure 3) He explained that when 55 percent of that total plant available water has gone away and been used, the plant experiences stress. So you really want to maintain your soil water content in your soil in the rooting zone between dual capacity and 55 percent of that in a sugarbeet crop.

An important point Tarkalson made about overwatering is “If you're moving water below that depth, everything is going with it: the water, the nitrogen, the nutrients. You're not going to recover most of it.”

Crop Information

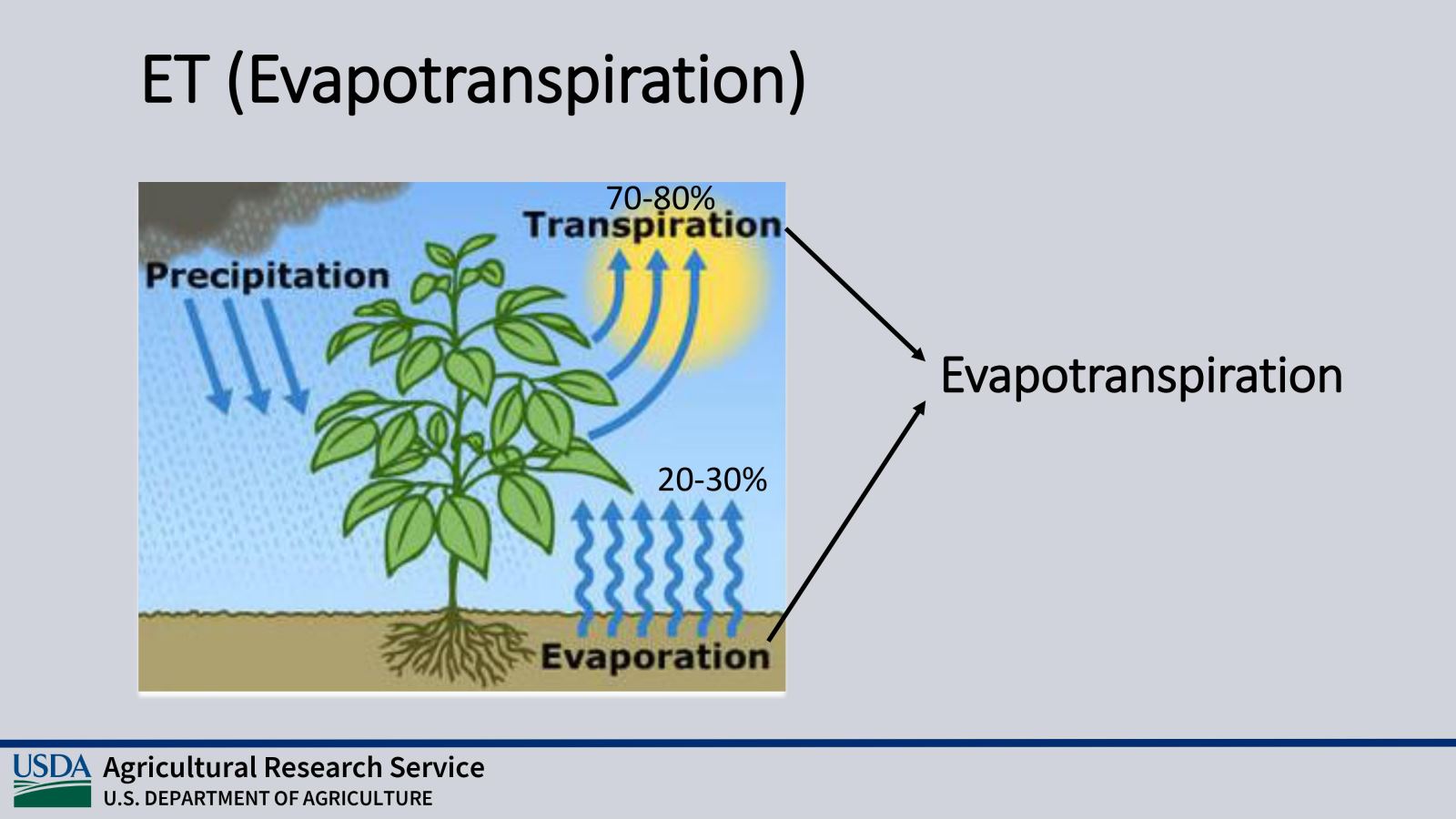

This part of the discussion touched on evapotranspiration (ET). Tarkalson pointed out that transpiration is when plants pull water up and flow it off through their leaves. He said, “About 78 percent of the water within the crop watering system is lost this way. And those losses are good. A plant has to move water from the root zone and has to get rid of it. That's part of maintaining a healthy plant. Some of the water is lost by evaporation from the soil surface. And that's something that is part of evaporation and taken into account with regard to crop water use. Take these two things, you add them together and that’s evapotranspiration.” (Figure 4)

He spent a fair amount of time talking about crop water use (Etc) and how, when using a specific model he and other researchers followed over the growing (and irrigation) season, when they followed that model, the crop did really well. Many of the parameters are already set up for the model so the grower needs only to access this information to know different crop water needs for different crops.

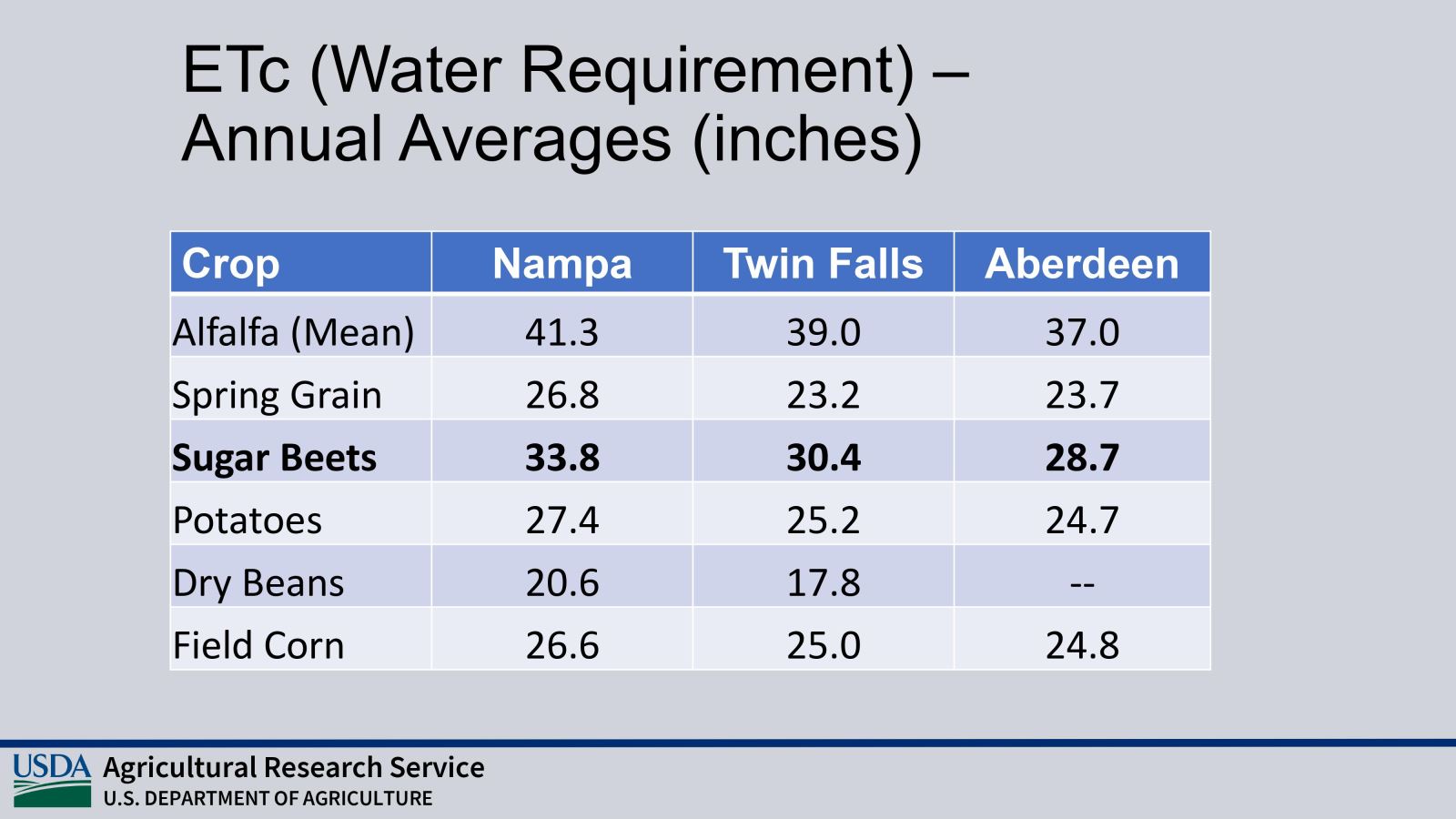

Of course, it’s more involved than that, but according to the charts showing the research he and others have done, the model does work when followed. He also showed a slide (Figure 5) of water requirements for various crops in Idaho for three different areas of the state. Referencing the chart he said, “This just shows you the average crop water requirements across the growing area for sugarbeets. As you go from west to east, that water requirement increases a little bit. This is an average over 10 years or so for showing you just the different values there.”

Technology Helps

Tarkalson talked about an impressive array of technology from the internet to apps to equipment that is available today to help growers as they try to figure out their irrigation needs.

Where can you find ETc values?

AgriMet (www.usbr.gov/pn/agrimet/).

Washington State University Irrigation Scheduler (http://weather.wsu.edu/is/).

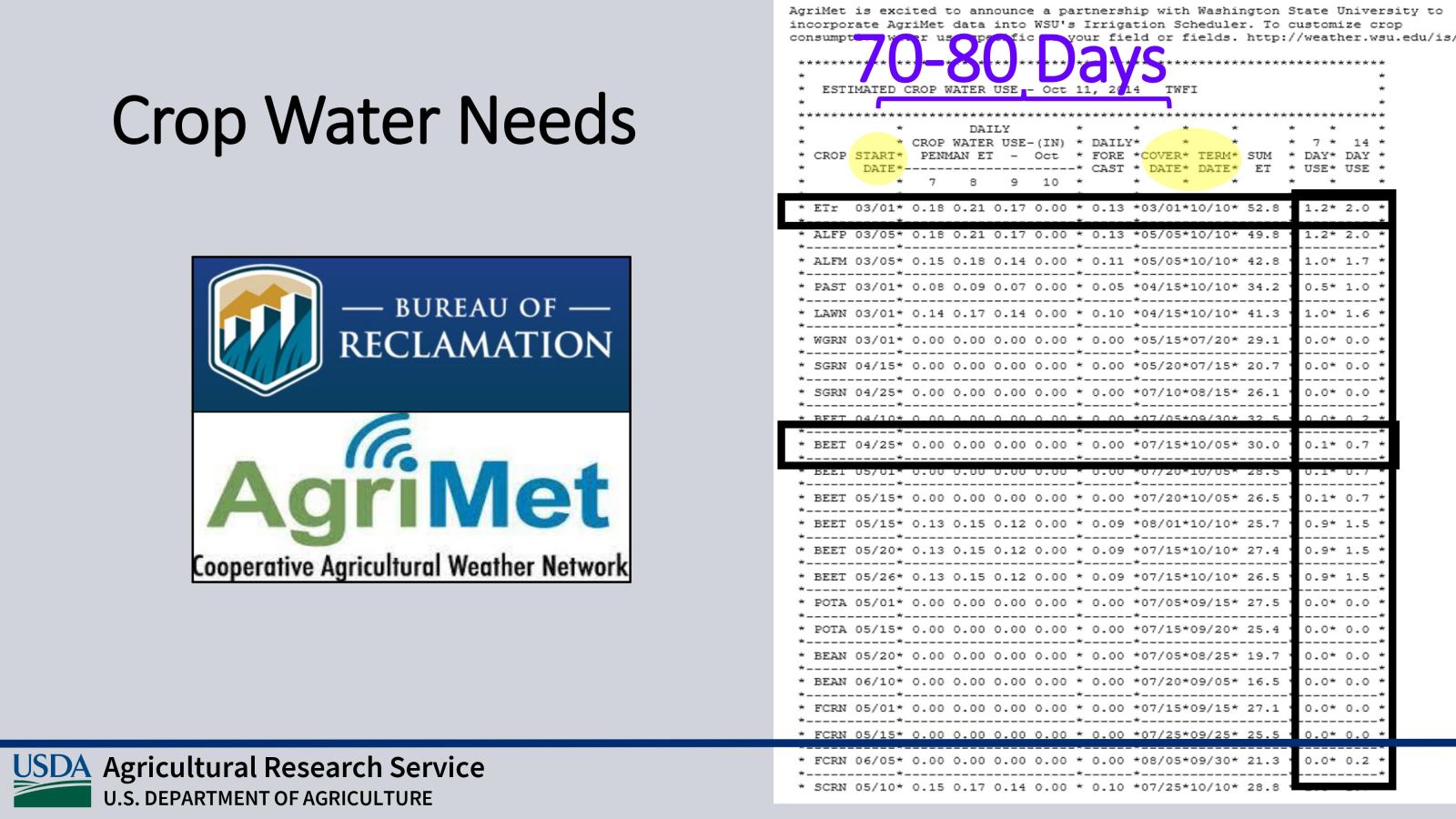

He pointed out that the Bureau of Reclamation, through its AgriMet website (a cooperative ag weather network) has weather stations across the entire western U.S.

“They have weather stations that are collecting the data necessary for the model to calculate reference ET for us. And also within their system, they'll actually incorporate the crop coefficient to give you crop water demand as well.” (Figure 6)

Something to keep in mind, Tarkalson said, is to add water onto your demand based upon the inefficiencies of your system. “So if you're going to be losing water from the air through evaporation, you have some run off or you're going to have some deep percolation perhaps on some furrow irrigated land, you’re going to have some inefficiency. So, for instance, if you're using a pivot, if everything is dialed in and you're estimating, you're about 90 percent efficient, that means you're losing 10 percent of water that's coming out of the system. So you need to add that 10 percent on top of your crop water needs.”

Finally, he covered equipment growers can purchase to test their soil moisture, another tool to help determine crop water needs.

For more information, you can reach Tarkalson at (208) 731-4962 or david.tarkalson@usda.gov.