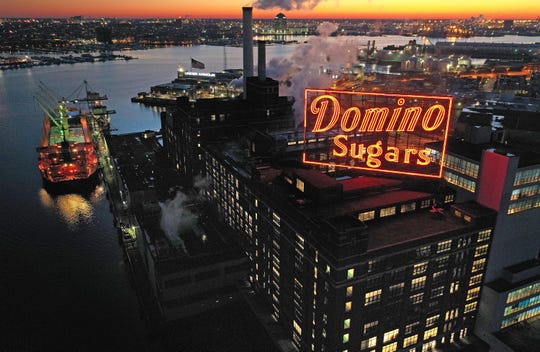

Under the neon Domino Sugars sign in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, a century-old refinery steadily produces the crucial ingredient in American candy, soda and other foods.

The already busy plant soon might need to burn even more calories.

Unusually bad weather around the country significantly hampered both U.S. sugarbeet and sugarcane crops last year, leading government officials to seek an 80 percent increase in raw sugar imports from Mexico. Extra cargo already has begun arriving by ship to the piers of a small number of processing plants, including Baltimore’s iconic Domino Sugar refinery.

The increase could push plants that normally run close to capacity to full capacity for an extended period this year, a churn that would be “historically unprecedented,” according to economists at the USDA.

At Domino, that means workers will skip every other weekend off, working 12 days in a row. That’s a strain, officials said, but for now at least it’s welcomed overtime at the Locust Point plant, one of the last major industrial operations on this largely gentrified part of the harbor.

The USDA economists noted that a terrible situation for farmers will be both a boon and burden for the refineries.

“It’s unusual to see refineries at 100 percent for a long period of time without problems or equipment breakdowns,” said Steve Haley, a sugar economist for a USDA board that analyzes supply and demand. “One could argue it’s unreasonable and there are going to be some significant problems.”

While harsh weather and bad harvests are not new, the level of devastation last year was far more widespread than usual, and some economists say it’s a possible harbinger of what’s to come as a result of climate change. The unprecedented situation has government and industry officials working without a recipe.

Wet and cold weather had the mostly unheard of effect of harming both sugar beet crops in northern states and sugarcane crops in Southern states. In Minnesota, for example, an extremely wet October followed by a hard freeze in early November meant sugar beet fields were too wet to harvest before the beets became frozen in the ground, according to a Minnesota Public Radio report.

Sugarbeets, grown across a broad swath of the upper U.S., from Michigan to Washington State, account for more than half of U.S. refined sugar. Cane grows in Florida, Louisiana and Texas.

The result was a 10-year low in production, said Rob Johansson, USDA’s chief economist, coming at a time when the nation’s sweet tooth has pushed demand far higher than a decade ago.

The sugar trade is governed under a long-standing USDA program aimed at protecting U.S. sugar farmers. Under a separate agreement signed in 2014, Mexico was given the first chance to fill shortages in the U.S. sugar supply.

It’s not yet known whether that country can spare enough to completely fill the gap, the USDA economists said. If not, supply could come from Brazil and other countries.

The USDA asked the Commerce Department to allow the extra sugar imports last fall – some raw sugar and some already refined into the familiar granular product familiar to consumers. There will be far more raw sugar among the extra imports, which would be minimally processed in Mexico before being finished at U.S. refineries.

With the increase, an estimated 1.8 million tons will arrive at U.S. ports this year from Mexico, up from about 1 million tons. Imports from all sugar-producing countries usually total 3 million to 4 million tons a year to supplement about 9 million tons produced domestically.

If demand continues to exceed supply on store shelves and in food manufacturing plants, more sugar imports could be allowed, but they could carry higher tariffs, potentially pushing up consumer prices, the agriculture officials said.

“We’ll be keeping an eye on things,” Johansson said.

Domino already is the nation’s largest marketer of refined sugar. Domino Food Inc. is owned by Florida-based ASR Group and produces those bright yellow packages of sugar sold at the grocery store. It also supplies sugar to food makers.

If the added imports successfully substitute for the missing domestic supply, food makers will go about producing not only sweets, but also bread, pasta and many other products that contain sugar, said Rick Pasco, president of the Sweetener Users Association, a Washington-based trade group whose members include food and beverage companies that use sugar.

But Pasco said he’s worried the plan is not flexible enough if something happens given the complicated trade rules.

Such uncertainty can put a strain on businesses, with smaller operations like a neighborhood bakery probably more severely affected in the short term. But big manufacturers also need to know that they can keep their production lines going, he said. Pasco said he’d like the USDA to start the process of allowing more sugar, both raw and refined, from other countries, rather than wait for shortages to increase.

“We’re hoping the refineries like Domino can crank out as much sugar as they can,” Pasco said. “Capacity is a real problem. Can they deliver? There was drought in Mexico. Can they supply enough? There are a lot of moving parts and overall it’s not a great situation.”